This is Part One of “Pure Fire,” a four-part series by Christopher Russell, the chef-owner of Red’s House, a Caribbean restaurant in San Francisco.

***

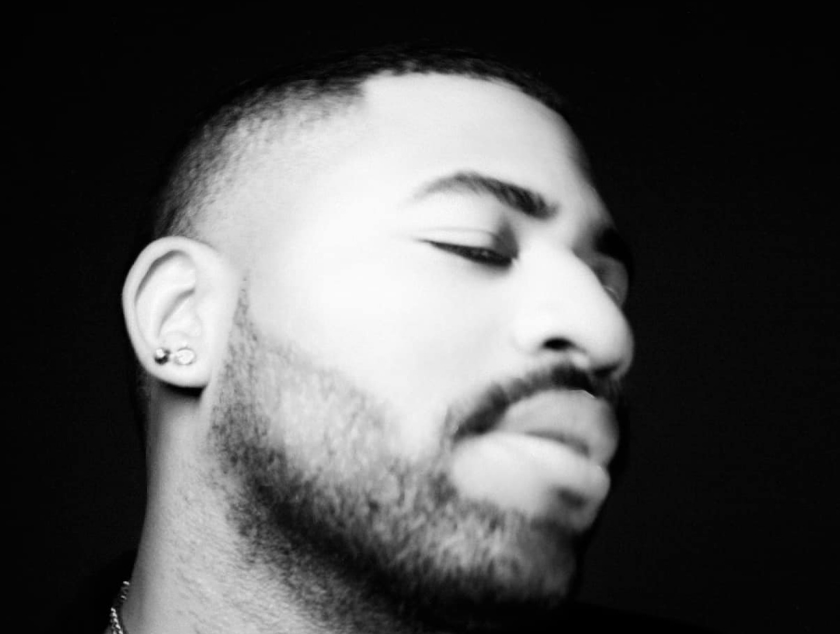

My name is Christopher Russell, and I’m one of the last remaining Black chefs in San Francisco. It’s 1:34 a.m., and there is a half-empty glass of Inglenook 2014 Cabernet Sauvignon to my right. My fingers are busy synchronized swimming on the keyboard in front of me. Today — well, it’s technically tomorrow — I’m already thinking about the next day’s service that will begin at my restaurant, Red’s House, in roughly 12 hours.

Red’s House is a successful failure in my eyes, an orphan with no permanent place to call home. A Caribbean restaurant serving up jerk chicken, Jamaican beef patties and more, it was inspired by my family’s notorious backyard gatherings in Crown Heights, where time didn’t exist as we laughed, danced, sang, shared dishes and told stories. It has taken years to get to the point of having my own restaurant and to be able to bring my mother Sharon on board, a dazzling chef in her own right. With her sagaciousness and my business savvy, I knew that Red’s House could become an institution within a city that suffers from a lack of diversity and authenticity.

Earlier this year, I was riding high with a successful pop-up, one that was finally starting to break even. There were new restaurant plans in the works, one-of-a-kind events, billboards, and endorsement deals — but then COVID-19 struck our delicate infrastructure and penetrated our way of life.

Here we are today located in what looks like an abandoned building from the outside; I guess maybe it adds to the mystery of our tightly run operation. Inside the walls of this commercial kitchen space in Daly City, quite literally a five-minute drive from the San Francisco border, is an entirely different story as many minority-owned businesses, ourselves included, are struggling to make the numbers work and keep businesses alive. So while customers enjoy our succulent jerk chicken, oxtail stew, and escovitch fish via takeout, I am currently drowning in debt, struggling to sleep at night, and fighting off the depression monster that I’ve carried on my back my entire life. I haven’t been paid in months and my team has significantly reduced in size.

***

To live and work in San Francisco is both an accomplishment and a misfortune, because as you may know, the Black population here is abysmal. From 2010 to 2017, only around 3% of residents aged 18 to 50 who moved to the city identify as Black, according to U.S. census data. I’m part of that 3%, having moved here in 2011.

I’m originally from Brooklyn, where I grew up within a very religious Caribbean community. My mother taught me how to cook — well, she more like graduated me to kitchen duties as her sous chef. I refer to her as Chef Sharon in and out of the kitchen because of her willingness to instill the generational skills she learned at a young age in me. It was then, in our tiny kitchen in Crown Heights, that I would aspire to become something great. My mother had a way about her, easing the most anxious person with only subtle gestures of reassurance. My mother’s grandmother taught her at age 10 to not only cook, but to also carry out the killing of the animal for the family meal. Close your eyes for a second and imagine a childhood filled with laughter, music, and the most amazing food aromas taking on a life of their own, as they dance to you from the kitchen. That’s what mine was like.

The only issue I had growing up was that I only had eyes for the other boys in class. My social circles were made up of purely girls with a dash of athletic guys here and there. I felt at ease around these girls, unguarded and protected. They knew my secret; they could probably smell it on me. I also realized that the most masculine guys that got to know me were actually very sensitive souls that wanted to keep me from harm. Actually, everyone seemed to know, except me.

That was the worst experience, because there you are as a young, awkward boy debating whether or not to come out, while everyone is already discussing it behind your back. My Caribbean family and community were heavy in the church, and being gay was not accepted — but as long as I kept that to myself, then it was alright.

Cooking became my escape into another world. There, I was free to experiment and create with what was available. I was 12 and discovering that there were many ingredients that reflected parts of me that I wanted so badly to cook with, to taste for the first time, and to bring out their full potential in my own way. Uncomplicated, no restrictions — just a boy, his pots, and the secret ingredients that would not only change the way I approached food but the way I thought about myself. I would take the subway into Manhattan on the weekends because I loved Central Park, the interesting characters I would come across on my adventures, and the New York Public Library where I would get enraptured by all the books. I started saving my allowance and sourcing ingredients that I could only read about in books. (Once I saved two months worth of allowance to buy a half-teaspoon of truffles.)

In the kitchen, I was in control and no one could tell me what to do. The rest of my life was very strict, with rules on top of rules, but in the kitchen, I was left to my own devices — and there was no rule book when I was alone. There was no right or wrong, just experimentations and discoveries. As I got older, I found a rhythm all of my own: The kitchen became my studio, a place where I could create art for people to consume.

***

The truth is that even before the pandemic hit, I was already having a hard time maneuvering the restaurant scene in San Francisco. My background is in social media and fashion, so there were a lot of restaurant people here that didn’t take me seriously and wouldn’t give me a chance to prove that I could cook with the best of them. Yet I’m so grateful to have gone through these rejections because I wouldn’t have gone through an important transition.

And I definitely wouldn’t be the chef I am today.

So this is my story.