Joseph Lee was one of Boston’s most successful hospitality entrepreneurs when he invented machines that transformed industrial breadmaking for the next century. But he didn’t sell them for crumbs.

In the early 1890s, Joseph Lee had a good problem on his hands. The owner of the bustling Woodland Park Hotel in Newton, Massachusetts, was producing too much bread.

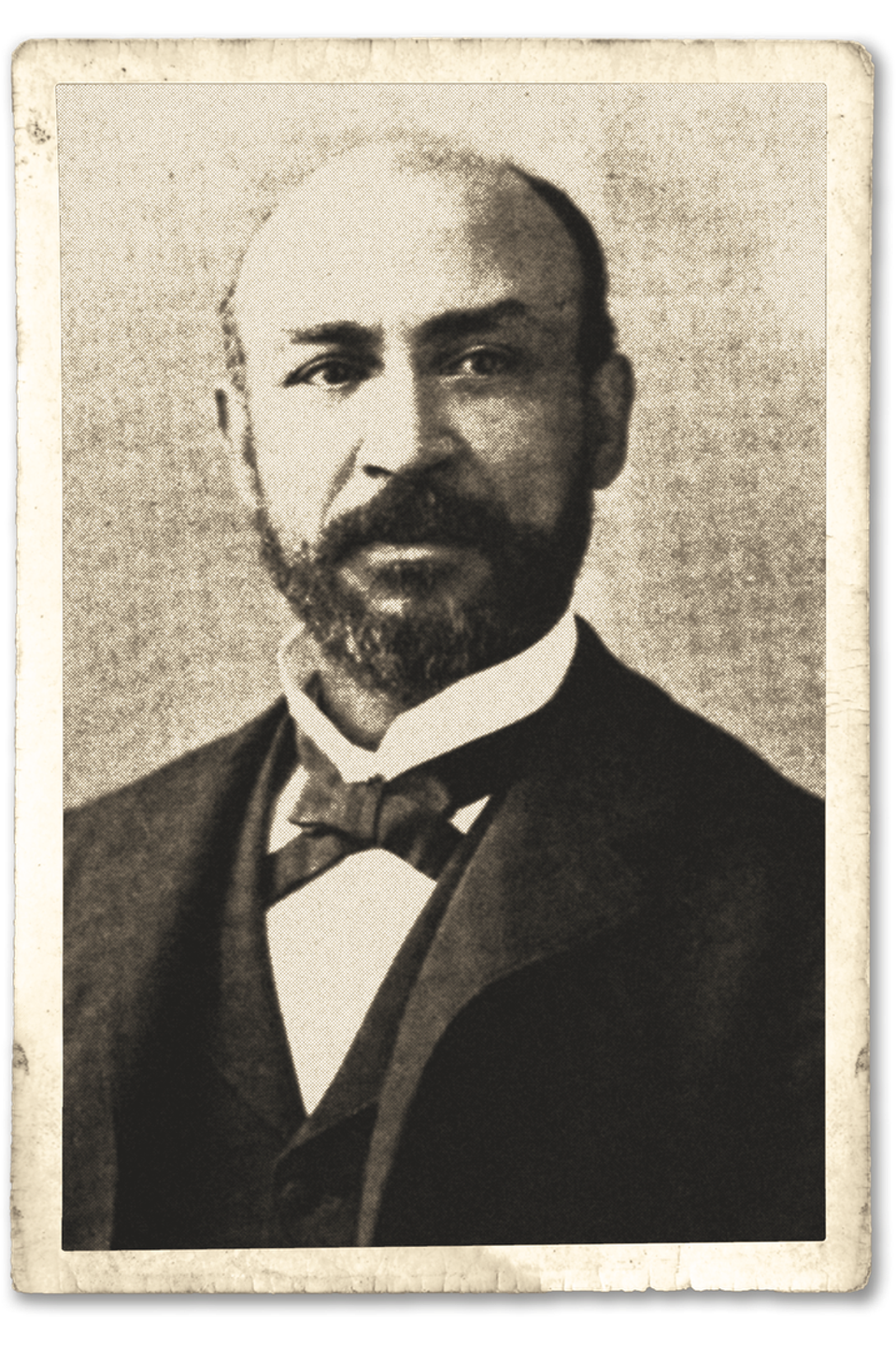

Born enslaved in 1849 South Carolina, Lee understood challenges far greater than an abundance of food. After working in kitchens as a child, he became a blacksmith during the Civil War before making his way to the North as a ship’s cook. He settled in Newton, where he took a job in a bakery and started a side hustle—selling food out of the boarding house in which he lived.

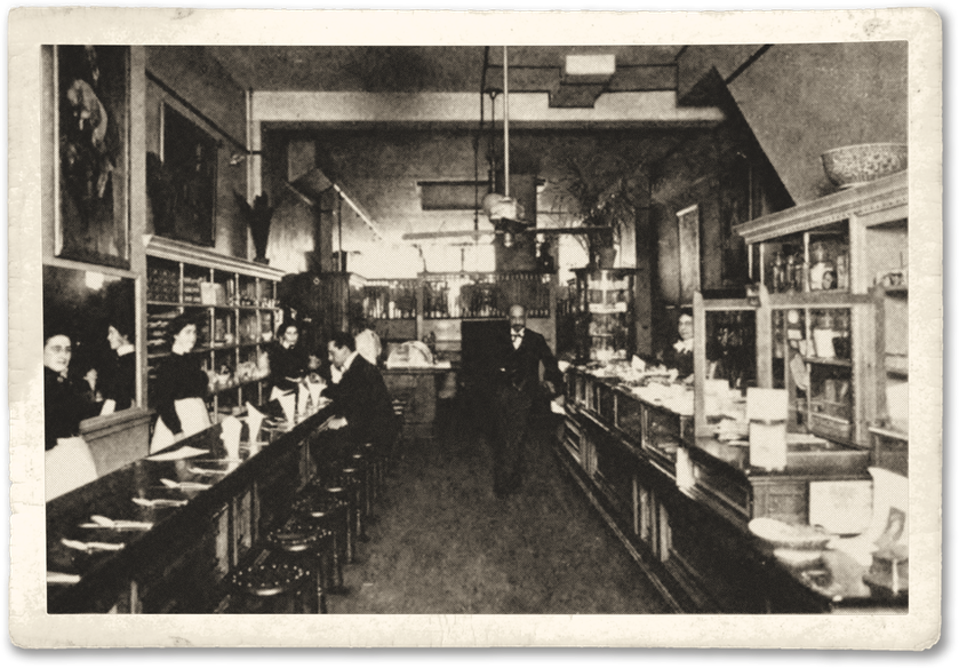

The experience helped Lee open his first real business, a small local restaurant, while still in his 20s. He eventually parlayed that success into the posh Woodland Park Hotel, a multiacre, dine-in resort and events venue with billiards rooms, bowling alleys and tennis courts. Lee’s hotel catered to Boston society and regularly entertained high-profile guests, including three U.S. presidents, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison.

The hotel was also the birthplace of Lee’s most important and lasting inventions—machines that transformed baking and food preparation for much of the next century. His first, an automated bread-kneading machine, yielded more bread than he and his staff could serve.https://0b264c953658320d541267eacef2d20c.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html

“Simple as this machine is, it is unique, and there is no competing mechanical device in existence that is similar to it or capable of performing the same work,” Colored American magazine printed in a 1902 May edition in reference to Lee’s automatic bread-kneading machine. It added: “Kneading done by it develops the gluten of the flour to an unprecedented degree, and the bread is made whiter, finer in texture, and improved in digestible qualities.”

It also preserved ingredients and saved time. The machine could produce 60 pounds more bread from each barrel of flour than could kneading by hand. And rather than let the extra bread to waste, Lee developed his second groundbreaking invention.

His automatic bread crumbing machine was the waste-saving solution that turned Lee’s superfluous day-old bread into the household staple we now know as bread crumbs, for everything from fried and battered fish to salad croutons. “In the colonial era, bread crumbs and milk were a fairly common breakfast, a precursor to cereals like Grape-Nuts,” says Boston University gastronomy professor Megan J. Elias—but a rise in the restaurant industry made an automated tool for bread crumbs particularly valuable. “There was probably an expanding market for bread crumbs in commercial kitchens,” Elias adds. “In your own home you use up the crumbs you have, but in a restaurant, you want a more reliable supply so that you know what you can put on your menu.”

Joseph Lee saw it as the perfect opportunity to make literal and figurative dough.https://embedly.forbes.com/widgets/media.html?src=https%3A%2F%2Fe.infogram.com%2Fb59a1f0e-dbf3-4651-9e59-a955a3c66f98%3Fsrc%3Dembed&display_name=Infogram&url=https%3A%2F%2Finfogram.com%2Fsobe-recircbanner_lt-1h984wojzwwzd6p&image=https%3A%2F%2Finfogram-thumbs-1024.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com%2F0463253f-4bcd-4c1b-9945-9106c08a6796.jpg&key=3ce26dc7e3454db5820ba084d28b4935&type=text%2Fhtml&schema=infogram

“African American people,” says Psyche Williams-Forson, the chair of American Studies at the University of Maryland, “have always been placed in positions of having to do more with less.”

It’s the framework that explains why “Black Americans were always inventing,” adds Kara W. Swanson, a law and history professor at Northeastern University. But proper ownership was hard to come by. “Many sold the rights to white men in part because they didn’t have the money to develop or because they were worried that people wouldn’t want to buy what they were inventing,” adds Swanson.

Countless Black Thomas Edisons produced transformative inventions in the late 19thand early 20th century that were either lost to history or outright stolen simply because of their race. “The offices of patent attorneys were in ‘white-only’ commercial districts, hindering African American inventors from applying for patents,” notes Lisa Cook, the author of a 2013 study of patent activity from 1870 to 1940.

Joseph Lee, however, defied the odds. In 1894, he successfully filed the first patent for his bread kneader, making him one of 92 Black patentees, according to data cultivated by Henry Baker, a Black patent examiner at the time. The same year, the only Black man in Congress, South Carolina Rep. George Washington Murray, inserted this list of patentees, including Lee, into the Congressional Record. With his momentum strong, Lee filed a second patent for his bread crumb machine the following year.

“You’ve got to give Joseph Lee his props,” says Ben Mchie, founder and executive director of The African American Registry. “This was done when food preparation was still subject to many human mishaps; there were no federal regulations—the Food and Drug Administration wasn’t initiated until 1906. There were all sorts of things that came into play that he foresaw, and he used his heart as much as mind to construct.”https://0b264c953658320d541267eacef2d20c.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html

Making Lee’s accomplishments even more impressive is that he didn’t have a formal education. He was largely self-taught, though he did attend some underground schools in the South. “He was special,” says Jerome Peoples, author of the 2011 biography, Lee’s Bread Machines. “We know that slavery had all kind of punishment, just the mental cruelty of it. But he was able to block out the distractions, and he didn’t give up.”

And competitors took notice of his innovations.

When food corporations started learning about Lee’s bread machines, they immediately realized the money that could be saved—and made. A true businessman, Lee wouldn’t sell his creations for crumbs.

In 1901, he formally assigned the patent rights to his bread-kneading machine to the newly formed National Bread Co. The company was backed with $3 million (about $92 million today) in investments, and Lee was made a stockholder. He also sold his bread-crumbing machine to Antrim, New Hampshire-based manufacturer the Goodell Co. and, eventually, those machines would be mass-produced by the Royal Worcester Bread Crumb Co. and marketed to hotels and restaurants across the country.

Beyond owning the patents for his machines, Lee had another major advantage over his fellow inventors: “Lee was already rich,” says Peoples. Thanks to his hotel, he was named one of Newton’s wealthiest men by the Boston Daily Advertiser in 1886. “He was confident, but he did not get complacent.”

Decades before the era of celebrity chefs, Lee’s cooking was held in high regard, particularly in Boston’s tony Back Bay neighborhood. His Woodland Park Hotel was regarded as having “the only genuine Philadelphia chicken croquettes and dressed terrapin in all New England,” M.F. Sweetser wrote in the 1889 King’s Handbook of Newton, Massachusetts, in whichLee received other accolades.

“Until the 1970s, the chefs were unknown—you didn’t know who was cooking,” explains James O’Connell, author of Dining Out in Boston: A Culinary History. “So Lee was the key person. He was the owner. He was the face of the place. I don’t know of anyone else who was Black running that significant of a hotel.”

An economic depression at the close of the 19thcentury forced Lee to give up the Woodland Park Hotel in 1896, but he remained in the hospitality industry, managing but not owning the fine-dining Pavilion Restaurant that overlooked the Charles River and Norumbega Park. With income from that business as well as his bread machines, he soon opened the Squanton Inn, a local summer resort, and his own catering company in Boston.

“Lee was evidence to white America of the abilities of Black Americans, abilities that they had been told explicitly they did not have.”

“That Lee had all these restaurants is not surprising—New England was one of the areas where you had a number of Black entrepreneurs who excelled in areas like baking and cooking and ran hotels and boarding houses,” says professor Williams-Forson.

“But this success is far more difficult for people to wrap their head around,” she continues. “Because to acknowledge those kinds of accomplishments flies in the face of everything that we’ve been taught about African American people as lazy, as unintelligent, as criminals. We have made incredible contributions to American society, but if you can keep those stories buried, then you can continue to push this one narrative that paints us in very particular ways.”

Joseph Lee upended those racist stereotypes. “Everything that Lee accomplished was accomplished in the face of anti-Black racism,” says Swanson. “He was evidence to white America of the abilities of Black Americans, abilities that they had been told explicitly they did not have.”

Despite being wealthy and successful in his lifetime—he eventually passed down his business to his children after his death in 1908—Lee remains largely unrecognized for his accomplishments today. He wasn’t inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame until 2019, but today’s generation of bakers still appreciate his legacy.

Chef Paola Velez, cofounder of Bakers Against Racism and executive pastry chef at Maydan & Compass Rose, appreciates bread-making by hand, but she remains in awe of how Lee advanced the industrialized kitchen. “Sometimes if I’m doing a class, I’ll show people how to knead dough by hand, and I forget how hard it is on my back muscles,” says Velez. “But I think about how much progress we’ve really made—that I could just put flour and butter and eggs and warm water and yeast in a mixer with a hook attachment and now I have beautifully consistent dough each and every time, all because somebody was bold enough to create something, and now we don’t know life without it.”https://0b264c953658320d541267eacef2d20c.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html

The team behind the newly founded Black Bread Co. in Illinois is also inspired by Lee’s pioneering spirit as they work to get their brand—the only Black-owned sliced-bread brand—onto shelves today.

“We are standing on Joseph Lee’s shoulders,” says Black Bread cofounder Jamel Lewis. And like Lee a century ago, Lewis adds, “We consider it a challenge; that’s why we took it on.”

And like the bread Joseph Lee made famous, they are ready to rise.

CultureX is a series that celebrates decades of forgotten Black entrepreneurs.

Source :https://www.forbes.com/sites/briannegarrett/2021/03/09/how-this-unsung-black-entrepreneur-changed-the-food-industry-forever-and-made-a-lot-of-dough/?sh=43b82fa37c92